This is the first of a four-part series, tying Botticelli’s Primavera with the role of images in society.

Botticelli is one of the main representatives of Renaissance art. His name is attached to the city of Florence, where his most notable works attract millions to the Uffizi galleries. His two 1480s masterpieces, The Birth of Venus and Primavera (or Spring in Italian), are two large paintings where crowds can still be seen gazing, observing, and inevitably, taking selfies.

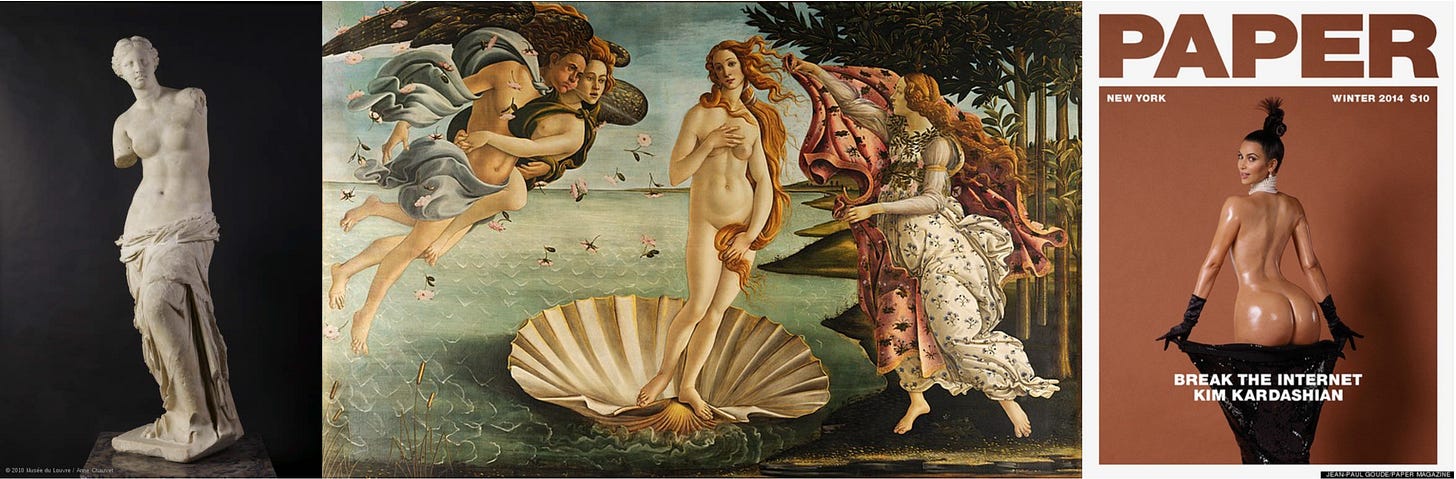

Venus’ reputation relies mostly on its historical significance and a sensual subject matter: it is the first representation of a female nude since Antiquity. The raw lines of her curved stance provoke us, seduces us. She connects the Ancient Greek admirer of the Venus de Milo to today’s worldwide web idolizing Kim Kardashian and her 2014 Paper Magazine cover. This triggers a past-present comparison. Do we realize photoshop works just like painting? Yet do we look at photoshopped pictures the same way we look at paintings?

When gazing at a nude in stone, or drawings, one cannot be fooled by the idealized, too-good-to-be-true beauty of classical nudes, for they are clearly human-made. The objectivity of the photograph, on the other hand, lets us believe everything it shows. Even though it’s been modified, it looks so real, and our instinct tells us it’s true. Are we, unlike our ancestors, surrounded by images confusing us, where the game of figuring out what’s real from fake overthrows the contemplative eloquence of beauty? Images used to make people spend hours with a single work. May it be praying, analyzing, or question the world around them, they were consumed with more time and diligence than the constant flow of Instagram stories and the omnipresence of advertisements capturing our attention for seconds only. Venus’s older sister, Primavera, has witnessed five centuries of use of images and provides clues to help us answer the questions raised above.

It is one of the most enigmatic paintings in history. No nudity, just poetry. Symbol of the city of Florence, its powers had long-lasting effects on me, from initiation to “slow art” to life-changing decisions. Her fame today began with its rediscovery in the 19th century, when a German scholar named Warburg and a newly unified Italian government were rewriting the pages of the Renaissance. Going further back in time, the context around its conception in 15th century Florence leads us to imagine its function as a pedagogical tool. Over the last five hundred years, this same painting embodies multiple meanings, each demonstrating a different purpose for the same color covered wooden panel.

This week, allow me to be your guinea pig. The personal relationship I have with Primavera can once again, show its importance through these words. My personal experience with Primavera is a human-scale proof of the Power of Images, a concept and eponymous book by David Freedberg. By looking at art from the viewer’s perspective, observing human interaction with these objects, we discover images can have a purpose, and it seems to be buried deep in the depths of our subconscious. All one needs is time and attention.

Next week, we look at the historical meaning of Primavera. Dedicated to art-historian Aby Warburg, he was the first to outline a detailed explanation of the painting. Understanding Warburg’s 19th-century context will show how the early modern era reinterpreted most of history. Reevaluating the importance of 15th century Florence, overshadowed by the traditional primacy of the Roman Catholic church and Raphael’s rooms in the Vatican, Botticelli became the flag bearer of these changes after centuries of being overlooked.

In the third week, starting with Warburg’s discoveries, we finally explore the painting itself. Focusing on its original context, we enter the private world of the almighty Medici. Primavera was born, its secrets will slowly dissolve in pure poetry and pedagogy.

In the fourth week, it will be time to reappropriate the painting for ourselves. Taking all the context into consideration, it will raise the question: what can Primavera teach us today?